|

Film Budgets: How Low Can You Go?By Brita BrundageI stumbled into the world of local filmmaking expecting to find a rag-tag collection of struggling artists who had pulled their films together with a combination of strong coffee, Scotch tape and old-fashioned gumption. But after the third filmmaker I spoke with directed me to his professional-level website complete with a full biography and images, I knew I'd made a preposterous assumption. Nobody, it seemed, was making films without money, and many of the productions cost a bit more chump change than I had envisioned. Poor artists might make paintings, but they certainly don't make films. Case in point: Hastings, N.Y., resident Peter Callahan entered his partially autobiographical film Last Ball into the festival. The feature-length story, he explained, shows a character whose "parents are pretty successful, driven people." The young lead character, "instead of going to a good college and leaving town...stays behind in the small town and starts driving a local taxi and ends up having an affair with a married woman." The story has a lot to do with his own life, the filmmaker admits. As he says: "It's about what happens when your friends head off to college and you stay behind."

Callahan may have driven a taxi while drawing inspiration for his hometown Westchester film, but he did strike gold in the end. A New York Times article about the film states that Callahan received local "investments" from $5,000 to $10,000 and one woman sent a check for $100,000 with the explanation that it would be "neat...to see Hastings on film." Local filmmakers without the backing to pull off such expensive projects face greater time restrictions and less room for expensive errors. While Callahan was able to employ professional actors like 18-year-old Charlie Hofheimer (who has appeared in Hollywood movies like Father's Day, and Wes Craven's Music of the Heart) other local filmmakers have fewer financial resources at their disposal. "The budget was very crunched," said Wesptort native Jarett Liotta, of his local feature film How Clean is My Laundry. His film also has an autobiographical bent--another mislaid working man, this time working at the laundromat, in the midst of wealthy Westport. Like Callahan, he once held the job himself, but he still hasn't found his sugar daddy.

Clarke Smith of Norwalk faced a similar predicament in making his movie, The Ethereal Plane. Shot almost entirely in Stamford, the movie takes a more imaginative twist than its counterparts--it focuses on a time machine which the lead character uses to go back in time to intervene with a murder he has witnessed. A bit more Hollywood-sounding perhaps, but Smith relied entirely on community theater actors willing to volunteer their time.

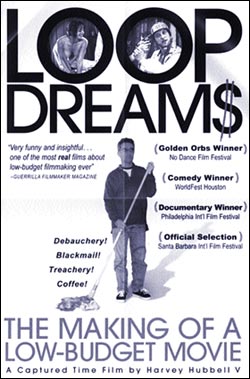

It seems the less money a filmmaker has available, the more tasks he must handle on his own. Writing is a given. In addition, Smith filmed his entire feature-length film himself and then edited it himself over the course of 16 months. While Smith majored in film in college, he says he "never worked at it on a professional level. Just as a hobby." After all this sweat, says Smith, "now it's a big hobby." On the other hand, Callahan, who made the rather pricey Last Ball, admits, "I couldn't even turn a camera on. I had no actual film experience other than writing screenplays." He defends his role, saying, "A lot of directors come from that background. They focus more on story than fancy camera work." That is, if they can afford to focus at all. The nature of a festival like the Director's View is that small budget and big budget will be judged on par--for first-time filmmakers, the experience is sure to be a learning one. While they may have been accepted into the festival, they are up against near-professionals with mile-long credentials. Some directors, like Harvey Hubbell V, who made Loop Dreams: The Making of a Low Budget Movie, simply have more experience. His film is done documentary-style, although it's better described as a comedy. Hubbell, his wife, Andie Hass, recently named 2001 Connecticut Filmmaker of the Year, Rhodes scholar and writer Jeremy Brecher, Ph.D., (author of Global Village, Global Pillage) and other film professionals filmed the documentary while Hubbell was assistant director for the film Blackmale, which was shot in Danbury. Loop Dreams recently won the gold World Medal for comedy in the New York Festivals.

What Loop Dreams captures in its frenzied, behind-the-scenes moments, is the time-consuming, brain-sapping effort required to actually make a movie. As assistant director, Hubbell could take his documentary camera places where other filmmakers would have been shut out. Loop Dreams is especially useful for student filmmakers. "We show this to a lot of the college kids," says Hubbell, "where the kids just want to go off and make movies and they think it's going to be really easy. But it's not so easy to put your head in your hands." How can small-budget directors remain competitive in the field? Reapply their creativity to making the dollars stretch. "Independents are some of the most resourceful people in the world," Hubbell affirms. It's more than just money that makes a film stand out--it's the quality of the writing, the sincerity of the actors and the creativity of the vision. Hubbell, who has won more than 40 film and video festival awards, including six Emmys for his documentary work, says this: "It's determination that you gotta stick with this project no matter what. And no matter what can be--floods and fires and crew mutinies. It really tests your passion."

Fairfield County Weekly home pageCopyright �2002 New Mass. Media, Inc. All rights

reserved. |